- Home

- Prue Mason

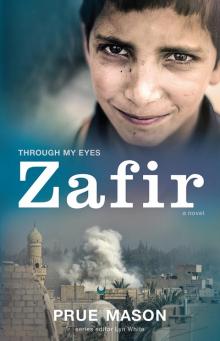

Zafir

Zafir Read online

TITLES IN THIS SERIES

Shahana (Kashmir)

Amina (Somalia)

Naveed (Afghanistan)

Emilio (Mexico)

Malini (Sri Lanka)

Zafir (Syria)

A portion of the proceeds (up to $5000) from sales of this series will be donated to UNICEF. UNICEF works in over 190 countries, including those in which books in this series are set, to promote and protect the rights of children. www.unicef.org.au

First published in 2015

Text © Prue Mason 2015

Series concept © series creator and series editor Lyn White 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia – www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 254 4

eISBN 978 1 74343 134 4

Teaching and learning guide available from www.allenandunwin.com

Cover design concept by Bruno Herfst & Vincent Agostino

Cover design by Sandra Nobes

Cover photos: portrait by Diyar Sarges, Syrian conflict by Getty

Text design by Bruno Herfst & Vincent Agostino

Map of Syria by Guy Holt

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

For Bassel and Lina

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Author's note

Timeline

Glossary

Find out more about …

Acknowledgements

Zafir shivered. It was an icy morning in the city of Homs and the wind felt sharp enough to strip the skin from his body. Tetah, his grandmother, had said it might even snow. Zafir hoped it would, but he wished winter didn’t have to be this cold. Although he was wearing a scarf, long trousers and a sweater under his school blazer, he still had to sit on his hands to keep them from turning into icicles as he hunched on the front seat of the old yellow taxi.

‘Is it going to snow?’ Zafir asked Abu Moussa, the taxi driver who took him to school every day. There was no bus from Al Waer and after what had happened in Dubai, Mum didn’t want to own a car.

‘It isn’t cold enough yet,’ replied Abu Moussa. He spat out the window. It was always down just for that purpose. A freezing draught blasted through the car. The cold air swirled around Zafir and made the gold-framed verse from the Qu’ran that hung from the rear-view mirror twirl like a mini merry-go-round.

They were travelling on the ring-road that circled the city. Although they had to travel further, it was a double-laned motorway and there wasn’t as much traffic so it didn’t take as long as driving directly through the city.

Abu Moussa was wearing his brown winter thobe, long gown, with a red-and-white checked cotton shemagh draped around his head and sandals without socks. Zafir wondered if Abu Moussa didn’t think it was cold because of the huge grey moustache that covered half his face.

‘Does the wind here ever stop?’ Zafir asked.

‘The bird flies higher into the wind,’ replied the taxi driver as if that answered the question. ‘Alhamdulillah, praise God! But if this saying is true then aeroplanes must watch out when flying over Homs.’ He laughed as if what he’d said was really funny. Zafir started to laugh as well. He couldn’t help it. Abu Moussa’s cheerfulness spread and warmed him.

Finally the taxi driver wiped his eyes with the end of his shemagh and pointed to a line of trees growing on the side of the motorway. None were completely upright: the trunks and branches leaned towards the east, clearly showing the direction of the prevailing wind that funnelled into the gap between the coastal mountains to the west and the north of Homs. ‘Such is the strength of the Homs winds,’ he said, ‘that all visitors remark on the bent trees.’

Zafir shrugged. He was a visitor once. He’d never noticed the bent trees but he’d liked Homs then. It used to be brilliant coming to stay with Tetah because as the only grandchild he got spoilt. She lived in the old area of the city that had winding, narrow streets built for donkeys, not cars. It was like going back in time. Pops was always happy coming back to his hometown and he took them to all the tourist places like Crac des Chevaliers, the famous crusader castle up in the hills. They always came in summer. The scent from the white jasmine that grew on every corner and along the streets was so strong that Zafir had never noticed all the bad smells from the oil refinery and the fertiliser plant or how much rubbish there was in the River Orontes.

Now, six months after the excitement of moving to Homs from Dubai last July, Zafir wasn’t so pleased about living here. Even Mum didn’t like it now and it had been her idea to move in the first place. Pops had found a job as the head doctor at the new training hospital in Homs, and it had seemed like a good idea to get away from Dubai after …

Zafir felt the pain again. But it had started to hurt less when he thought about the car accident. About how when the police came to tell them that Giddo and Siti, Mum’s parents, had been killed, Mum had not believed it until Pops came home from the hospital and said it was true. The worst thing was that Giddo had been about to retire from his job as director of the Dubai Hospital where he’d worked for over thirty years. He and Siti were always talking about returning to live in Damascus, especially since Mum’s only brother, Uncle Ghazi, had left Dubai to go to university there three years ago. Mum always said that her parents never would leave Dubai. She was right.

In the end, it was Mum, Pops and Zafir who had moved to Syria because Mum found it too hard to live in Dubai without Giddo and Siti. She’d said that in this new year, 2011, everything was going to get better. Zafir hoped she was right, but he still missed Dubai and his friends.

The burbling roar of a car engine behind them cut into Zafir’s thoughts. He couldn’t see the car because in the lane directly behind them was a silver-bellied petrol tanker, probably on its way from the refinery to Damascus, and alongside them, blocking anyone from passing, was an old farm truck full of potatoes with a cage of chickens perched on top. Zafir knew the chickens would be off to be sold at Maskuf market in the Old City, which was close to Hamidiyeh, the Christian quarter, where Tetah lived. A long, loud blare behind them all made the farm truck accelerate. It cut in front of them, making Abu Moussa mutter under his breath. A red car,

a Russian-made Lada 112 with dark windows and fat gold-rimmed tyres, raced by, the engine growling like an angry beast.

‘Nice car,’ said Zafir.

Abu Moussa pulled out from behind the farm truck and sped past it, waving his hand out the window at the farmer, who took no notice of the angry gesture. The red Lada was not far ahead of them.

‘Shabiha.’ Abu Moussa spat out the window, then started to sing. ‘Wain inti halla’a, where are you now?’ he wailed.

The brake lights of the red car ahead came on suddenly. Abu Moussa pressed hard on the taxi’s brakes. The back door of the Lada opened and a pile of clothes landed with a flop on the side of the road. The Lada accelerated away.

It was only when Abu Moussa pulled on the steering wheel so that the taxi swerved around the bundle that Zafir saw a hairy arm flung out. Then he saw that attached to the pile of clothes there were two legs. One foot still had a sandal on it.

‘We’ve got to help,’ shouted Zafir when his brain finally registered what he had witnessed. He had never seen a dead body before. ‘We must take that man to hospital. Pops will help him.’

Abu Moussa kept driving and singing, looking straight ahead through his large dark sunglasses.

Zafir could feel the pulse in the side of his head throbbing. He wanted to scream at Abu Moussa, but Pops had drilled into him that you have to stay calm in an emergency. He said that people could die if everyone around them panicked.

Stay calm, Zafir tried to tell himself, but instead he found himself thumping the dashboard with his fist.

‘We’ve got to stop.’ His voice sounded shrill to his own ears. They had to stop because that was the other thing Pops had always said – you might be the only one around who could save a person’s life, even if all you did was call the Red Crescent ambulance.

Of course! Zafir pulled out his phone. Was the number ‘999’ here, like it was in Dubai? Then he had a better idea. ‘I’ll call Pops,’ he said. ‘He’ll know what to do.’

But before he could dial any number, Abu Moussa stopped singing.

‘With all respect to the honourable Dr Haddad, he cannot help that man.’

‘Do you think he was dead?’ Zafir asked, still hardly able to believe what he had seen. ‘We still should have stopped.’

Abu Moussa shrugged. ‘The shabiha has taught that man a lesson they believed he needed to learn.’

‘The shabiha? Who are they? And why would they do something like … like this?’

‘Forget them,’ said Abu Moussa. ‘You aren’t old enough to know about such things.’

‘I’ll be thirteen in ten days,’ said Zafir. He’d be glad not to be twelve anymore. It was an age when everyone thought you were too young to be told anything.

From behind them they heard the sound of sirens.

‘The shurta, police, are coming,’ Zafir said. He was relieved. ‘They’ll take care of the man.’

Abu Moussa spat again and then, in the most serious voice he had ever used with Zafir, he said, ‘Zafir, this is shabiha business. For the sake of yourself and your good family you must not remember what you have seen. Ahsan lak, it is better for you.’

The image of the outflung hairy arm and one bare foot, the other with a sandal on it, was etched into Zafir’s brain. He was grateful now that he’d never seen the man’s face. What if his eyes had been open?

Zafir shivered. ‘I guess the shurta will catch them.’

Abu Moussa snorted and then started wailing about love again. Zafir couldn’t hear the sirens anymore and the usual stream of cars and trucks were going about their business like nothing had happened. Like nothing was wrong. Zafir wondered why no one ever talked about anything important that happened in Homs. Uncle Ghazi had said that foreign media called Syria the ‘Kingdom of Silence’ – was this what he meant?

The taxi slowed and they took the exit to the International School. When they’d first come to see the school five months ago, Mum had gone on about how wonderful it was to be outside the city, surrounded by farms that grew olives and grapevines. She had even said that maybe, later on, they could buy a small farm in this area and she could keep a donkey. She’d always wanted a donkey and a farm would be close enough for Zafir to walk to school. Pops had looked at Zafir and winked. It had been good to see Mum happy, but they both knew this was just another one of her crazy ideas.

As they approached the school they joined the long queue of cars and buses. Finally, they were waved through the boom gate by two security guards dressed in khaki uniforms, guns slung over their shoulders. The school was surrounded by a high concrete wall and a long driveway ran between neat gardens to the reception area – but that was only for visitors and students with more important parents. Abu Moussa took the right-hand lane to the spot where most of the students got dropped off.

For the first couple of weeks, Zafir had dreaded getting out of the taxi. Mum had thought it would be easy for him to settle in because the school was part of the same international school group that he’d gone to in Dubai, but she was wrong. It was just luck he’d made even one friend, and that was only because of an Apple sticker on his bag that he’d forgotten was there. Rami, who had the locker alongside his, had seen the sticker and whispered the first of the many secrets Rami seemed to have: he was actually related to one of the founders of Apple, Steve Jobs, because his mother was from the Jandali tribe in Homs and so was the man who was Steve Jobs’s real father. Zafir had to agree that was impressive.

‘I will be here to pick you up at four, inshala, if God wills, Zafir,’ said Abu Moussa as they pulled up.

‘Okay. Ma’a salaama, goodbye,’ said Zafir as he dragged his bag out of the back seat.

‘You’re late. I was beginning to think you’d gone back to Dubai.’

Zafir turned and saw Rami, his face round as the moon and split by his wide grin.

‘I wish,’ said Zafir. Immediately the cheerful look disappeared and Zafir felt guilty. It wasn’t just that Rami was Zafir’s only friend – Zafir was Rami’s only friend too.

Zafir had noticed that other students avoided Rami and he’d heard some calling him an Ibn al Homar, son of a donkey. Zafir didn’t like to ask too many questions because he knew that Rami’s family life wasn’t that happy either: his mother was always busy with his younger brothers and sisters; his stepfather, who was a naqib, captain, in the military sometimes beat him; and his real dad was dead.

Zafir and Rami fist bumped. Rami insisted they do this whenever they met because it was something Americans did and he was crazy about anything to do with the USA. He was excited Zafir had been to the States even though Zafir had only been eight years old. They’d visited friends of Mum and Pops, Aunty Leila and Uncle Vahid, who had immigrated to Chicago. From the way everyone talked about America, Zafir had thought it was going to be much better than Dubai. But it wasn’t. The air was smoky and the people were unfriendly and stared at them like they were weird because Aunty Leila wore her headscarf. It didn’t matter what Zafir said though. Rami still wanted to live in America one day.

‘I need to ask you something,’ said Zafir. ‘In the locker room.’

Rami lifted one eyebrow. That was the code Rami had told Zafir to use if he wanted to ask a question about anything to do with Syrian politics. Rami had said you had to be careful what you talked about because even innocent words could be made to sound guilty, and everyone here spied on everyone else. Rami like to spy on his own stepfather. Sometimes he got caught and came to school with bruises.

Neither of them spoke as they threaded their way between groups of students – girls who were giggling and whispering and boys who were jostling each other – towards the boys’ locker room.

As Zafir pushed open the door he was nearly hit by a flying pencil. The cousins Murshid and Mustafa and their gang were having a mock spear fight with pencils. Zafir used to do things like that with his friends in Dubai.

‘Maawaa’ez, goats,’ Rami whispered in Zafir’s ear, although there w

as no chance of anyone overhearing them with boys yelling, metal doors clanging shut and bags being thumped onto the tiled floor.

The locker room was so noisy it was the best place to tell secrets.

‘Okay, spill,’ said Rami as he pushed his bag into the locker.

‘Who are the shabiha?’

Rami swung around, eyebrows raised.

‘Keep your voice down,’ he hissed. ‘How many times do I have to tell you? The walls have ears.’

Before Zafir could say a word the door behind them burst open.

‘Bas, enough!’

There was sudden silence in the room as Mr Omar, the sports coach, strode in. Had he been listening? Zafir felt his skin prickle. Could Mr Omar be a spy? Would he tell someone that he’d heard Zafir asking about the shabiha?

Then Zafir realised Mr Omar was looking at the boys throwing the pencils.

‘Is this the way for gentlemen to act?’

No one spoke.

‘Who started it?’

Everyone stood silently, heads down, avoiding Mr Omar’s stare and each other’s.

‘If you don’t tell me, you will all be on detention.’

Zafir saw Mustafa look over.

‘It was him,’ Mustafa said, pointing at Rami.

‘Is this true, Al-Atassi?’ asked Mr Omar, even though he looked as if he didn’t believe it.

Rami nodded. ‘Yes, sayidi, sir.’

‘Okay, if you insist. Report to me after school. You can do extra swimming training.’

‘But it wasn’t him!’ Zafir burst out. He hated seeing his friend being picked on for no reason.

‘Would you tell me who it was then, Haddad?’

Zafir felt the eyes of all the boys on him and he saw Rami shake his head.

‘I don’t know,’ Zafir mumbled. That was the problem. He didn’t know what it was, but it was like there was something about Rami that no one was telling him.

‘Do you also want detention, Haddad?’ Mr Omar asked, but he didn’t wait for an answer. He turned and strode out of the locker room.

None of Murshid’s gang looked at Rami, not even to say thanks for getting them off the hook. Zafir heard Mustafa jeer, ‘Ibn al Homar.’

Zafir

Zafir Camel Rider

Camel Rider